India’s successful space mission is the latest manifestation of a renewed interest in lunar exploration, driven by national pride and strategy.

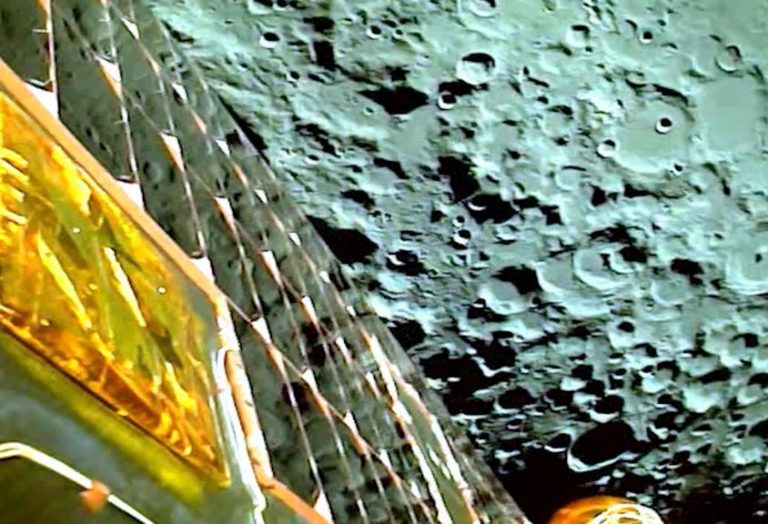

As the Financial Times reported, cheers erupted across India when the Chandrayaan-3 lander softly touched down on the lunar surface on Wednesday. “India is on the moon,” said the head of the Indian Space Research Organization, smiling and looking relieved.

The feeling of writing a new chapter in space history was indescribable — not only because India is the fourth country to land on the moon, after the United States, China and Russia — but because the Chandrayaan-3 landing took place near the unexplored South Pole.

India: Chandrayaan-3 successfully lands on the south pole of the Moon

But it certainly won’t be the last. Half a century after the end of the Cold War-era space race between the Soviet Union and the United States, an unprecedented number of nations are preparing for lunar adventures of their own.

New heroes

This weekend, Japan’s space agency is set to attempt an uncrewed moon landing, while South Korea plans to do the same. other countries. Canada, Mexico and Israel plan to send rovers to explore the lunar surface, while six international space agencies are working with NASA’s Artemis program, which aims to return humans to the moon by 2025. Meanwhile, China plans to send astronauts to the lunar surface. by 2030.

During the 1960s, when the United States and the Soviet Union raced to be the first to set foot on Earth’s only natural satellite, lunar exploration was primarily government-led and carried out by national space agencies. Although there are technological and financial benefits to the space programs, going to the moon was mostly about national pride.

More than half a century later, the main characters and motives have changed. While exploration, including lunar missions, continues to be dominated by major economic powers, the use of space in general has expanded to include many countries and private companies.

“Space technology has come down a lot in cost, and in some ways it’s been commercialized,” says Brian Weeden, program director at the Secure World Foundation, a US think tank focused on the sustainable use of space. “And that’s also why we’re seeing more countries building launch vehicles.” . . And show a special interest in space. And when they’re interested in space, the moon appears as a lofty but achievable goal.”

Aside from prestige — which remains an important factor for a moon landing — Weeden says many lunar missions aim to identify “what’s really useful.”

Of particular interest was the choice of India to land in the Antarctic. When the last Apollo mission left the Moon in 1972, scientists considered it a dry, barren place. But since then, explorers have shown that large deposits of water ice and rare-earth minerals could be hiding in cold, dark craters in Antarctica.

Both China and the United States want to use the area as a base for exploration of the far reaches of the Moon, with the long-term goal of learning how to live and work on another planet. If the precious water is not used for drinking, it can be decomposed into hydrogen for fuel or oxygen for breathing. The hope is that with permanent presence, more valuable resources can be found on the Moon to support missions that explore further into deep space.

NASA estimates that the development of reusable commercial rockets, such as the SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket, has reduced the cost of launching—per kilogram of payload—to so-called low Earth orbit by 95%. Private sector involvement in the development of lunar mobility and communications services promises to do the same.

difficulties

India was successful this week, but only after the failure of a previous mission in 2019. Days before the Chandrayaan-3 spacecraft touched down, the Russian Luna-25 spacecraft spun out of control and crashed.

Yuri Borisov, head of Russia’s space agency Roscosmos, blamed the failure on the country’s 50-year hiatus in the moon programme. “The invaluable experience accumulated by our predecessors in the 1960s and 1970s was virtually lost when the program was discontinued,” he said.

But the risk of failure has not deterred China, the United States or countries like India, who seek the prestige that a successful lunar mission would bring. And they don’t seem bothered by the uncertainty of what these costly projects might lead to. “If you were a big power on the moon, you would have a lot of influence in determining the details of managing the moon,” says Bowen.

The “war” has already begun. It is no longer just between the United States and China. India also aspires to send humans into space, and its low-cost approach has proven very successful so far. The Chandrayaan-3 mission cost $73 million, a fraction of the cost of other landings.

“Hipster-friendly coffee fanatic. Subtly charming bacon advocate. Friend of animals everywhere.”

More Stories

F-16 crashes in Ukraine – pilot dies due to his own error

Namibia plans to kill more than 700 wild animals to feed starving population

Endurance test for EU-Turkey relations and Ankara with Greece and Cyprus