The skeletal remains of a woman discovered at a Bronze Age burial site known as Camino del Molino, located in Caravaca de la Cruz in southeastern Spain, bore two holes that baffled scientists, who concluded that the woman had undergone two head surgeries!

According to scientists who examined the bones, the woman’s age ranges between 35 and 45 years, and she was discovered in a burial site that was used from 2566 to 2239 BC. Along with 1,348 other people.

But what sparked researchers’ interest in her case was a series of modifications her skull appears to have undergone, which appear to be surgical procedures that involve drilling or scraping holes in the skull to expose the dura mater, the outer layer of tissue. Surrounding the brain and spinal cord.

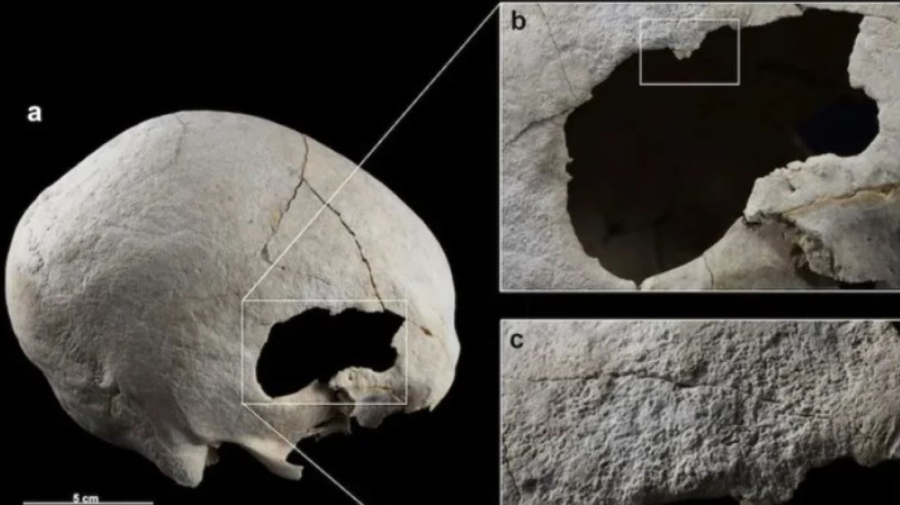

The scan also showed two overlapping holes between her temple and the top of her ear. One slot was 53 x 31 mm wide, while the second was smaller at 32 x 12 mm.

The researchers ruled out the possibility that these holes were the result of trauma, as there were no fractures and each hole had well-defined edges, so they concluded that the holes were the remains of two separate surgeries.

“We found two distinct holes, resulting from two different interventions,” said Sonia Díaz Navarro, a postdoctoral researcher in the Department of Prehistory at the University of Valladolid in Spain.

Based on the holes, along with the “slanting direction of the hole walls,” the researchers determined that the holes were made using a “scraping technique.”

“This involves stone grinding [πέτρινου] “An instrument has a rough surface against the vault of the skull, gradually abrading it along its edges to create the hole,” Diaz Navarro said.

“To perform this surgery, a person would likely have been severely restrained by other members of the community or previously treated with a psychoactive substance that would dull the pain or render them unconscious,” he continued.

He survived the operations

In fact, as everything shows, the woman survived both operations, as her skull appears to have healed, and researchers believe she lived for several months after the second surgery.

Diaz Navarro said documentation of prehistoric surgery is “rare,” especially in this area of the head known as the temporal region.

In the Iberian Peninsula, punctures were performed in the frontal and parietal (upper) regions of the skull.

The researcher stressed that the risks of working in this area include “the inherent challenges associated with accessing this area through the scalp.”

This area in particular has many blood vessels and weak muscles and can bleed easily during surgery.

However, prehistoric treatments using scraping technology were far more successful and safer than digging. Ancient surgeons generally did not damage the meninges or the brain, so women were less likely to develop potential infections after surgery. Diaz Navarro explained that using sterile tools and plants with natural antibiotic properties can help limit potential infections.

Unfortunately, researchers are not sure why the woman had this surgery. Although her skeleton showed healed rib fractures and some tooth decay, these health problems were likely unrelated.

“The high frequency of injuries recorded in skeletons from Camino del Molino leads us not to rule out the possibility that the operation was performed after the injury,” Díaz Navarro noted.

Surgery would have eliminated any evidence of bruising or wounds, and damaged bone fragments may have been removed during the procedure.

“Total alcohol fanatic. Coffee junkie. Amateur twitter evangelist. Wannabe zombie enthusiast.”

More Stories

Is this what the PS5 Pro will look like? (Image)

Finally, Windows 11 24H2 update significantly boosts AMD Ryzen – Windows 11 performance

Heart Surgeon Reveals The 4 Things He ‘Totally Avoids’ In His Life