Edited by: Gianna Merat

In a sketchy laboratory located between the campuses of Harvard University and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, a team of scientists seeks to discover the next billion-dollar drug.

The group, which has secured $500 million in funding from some of America's richest business families, has caused a stir in academia with its seven-figure fees to lure highly credentialed university professors into a lucrative bounty hunt.

The goal she sets for herself is: to avoid the barriers and red tape that slow down the traditional paths of scientific research at universities and pharmaceutical companies to discover dozens of new drugs that can be produced and sold quickly.

Many former academics have founded biotechnology companies, hoping to strike it rich with a major discovery. This team, called Arena BioWorks, has not one idea, but a big checkbook.

“I don't apologize for being a capitalist, and this motivation on the part of the group is not a bad thing,” said technology mogul Michael Dell, a major backer of the group. Others include the heiress to the Subway sandwich fortune and owner of the Boston Celtics.

The problem is that, over the decades, many drug discoveries not only came from colleges and universities, but also generated profits that helped fill their coffers. The University of Pennsylvania, for example, said it won hundreds of millions of dollars for research into mRNA vaccines used against Covid-19.

Under this model, any such windfall would remain private.

Arena has been operating in stealth mode since early fall, before unrest broke out in colleges bordering Israel and Gaza. But the motivation behind it, say the researchers who moved to the new lab, is getting stronger as the reputations of higher education institutions take a hit. They say they are frustrated by the slow pace and administrative turmoil at their previous employers, as well as what one new hire, Keith Young, described as “terrible” wages at Massachusetts General Hospital, where he worked before Arena.

Dr. said. Yang, a pathologist who helped design the gene-editing tool CRISPR. “Now the model has been turned upside down.”

The motivation behind Arena has scientific, financial and emotional components. Early backers first floated the idea at a discussion in late 2021 at a mansion in Austin, Texas, where Dell was joined by early Facebook investor Jim Breyer and Celtics owner Steve Pagliuca.

Mr. Pagliuca has donated hundreds of millions of dollars to his alma maters, Duke and Harvard, most of which is devoted to science. This earned him seats on four of the foundation's advisory boards, but he began to realize that he had no concrete idea what all the money was about, other than his name on a few plaques outside various university buildings.

Over the next few months, these early backers teamed up with a Boston businessman and trained physician, Thomas Cahill, to come up with a plan. Dr Cahill said he would help find disaffected academics willing to give up their grueling tenure at the university, as well as scientists from companies such as Pfizer, in exchange for a large share of the profits from the drugs they discovered. Arena's billionaire backers will keep 30%, with the rest flowing to scientists and overhead.

Speculative science, of course, is nothing new. The $1.5 trillion pharmaceutical industry provides ample evidence. Entrepreneurs like Jeff Bezos and Peter Thiel have poured hundreds of millions of dollars into startups trying to extend human lifespan, and several pharmaceutical companies have raided universities in search of talent.

A large proportion of medicines come from government or university grants, or from a combination of the two. From 2010 to 2016, every one of the 210 new drugs approved by the Food and Drug Administration was linked to research funded by the National Institutes of Health, according to the scientific journal PNAS. A 2019 study by former Harvard Medical School dean Jeffrey Flair said the majority of “new knowledge” about biology and disease came from academia.

This system has long-term advantages. Universities, generally helped by their non-profit status, typically have low-paid research assistants to help scientists with early-stage research. From this model pioneering drugs were born, including penicillin.

The problem, scientists and researchers say, is that there may be years of waiting for institutional approvals to move promising research forward. The process, aimed at clarifying unrealistic proposals and protecting security, can involve writing lengthy articles that can consume more than half of some scholars' time. By the time funding is complete, the original research idea is often already outdated, triggering a new round of grant applications for projects that will almost certainly be outdated over time.

Stuart Schreiber, a longtime Harvard-affiliated researcher who left to become chief scientist at ARENA, said his bolder ideas rarely find support. “I got to the point where I realized the only way to get funding was to apply to study something that had already been done,” Dr. Schreiber said.

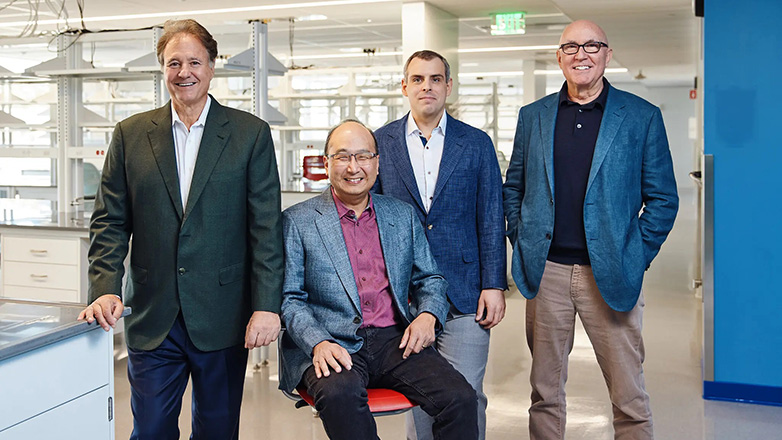

The group of Dr. Schreiber — a chemical biologist who is a pioneer in fields such as DNA testing — has helped attract nearly 100 researchers to the arena. Harvard declined to comment on his departure and the departure of others he helped attract.

An air of calculated secrecy surrounds Arena's operations. Dr Young, who resigned last year, said he did not tell his former colleagues where he was going and that many of them asked him if he was terminally ill. doctor. Cahill said that many of the scientists he hired were quickly denied access to university email and received severe legal threats if they tried to hire former colleagues — a common occurrence in a business world that preys on academia.

Arena BioWorks' first billionaire backers include Steve Pagliuca, owner of the Boston Celtics, Thomas Cahill, Stuart Schreiber, Keith Young, and Elizabeth DeLuca, the widow of the Subway chain's founder, who have each invested $100 million and expect to triple their capital. Invest in later rounds.

In confidential materials provided to investors and others, Arena describes itself as a “privately funded, fully independent public corporation.”

Arena's backers have said in interviews that they do not plan to end their college offers completely. Dr. Schreiber said it will take years — and billions of dollars in additional funding — before the team knows whether their model has led to any worthwhile drugs.

“Will it be better or worse?” Dr. Schreiber said. “I don't know, but it's worth a try.”

With information from the New York Times

“Avid problem solver. Extreme social media junkie. Beer buff. Coffee guru. Internet geek. Travel ninja.”

More Stories

In Greece Porsche 911 50th Anniversary – How much does it cost?

PS Plus: With a free Harry Potter game, the new season begins on the service

Sony set to unveil PS5 Pro before holiday season – Playstation