David Hockney, Britain’s most important living artist and one of the most influential artists of the twentieth century, narrates his biography through an exhibition of painted portraits, in a dazzling display of his art.

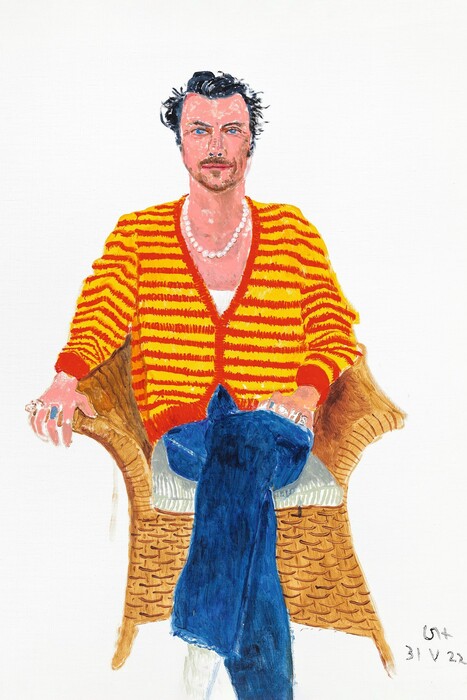

At 86, the eccentric painter, draftsman and engraver still paints Harry StilesHe plays with the iPad, draws like a teacher, and when he picks up his pen or pencil, he has no competition.

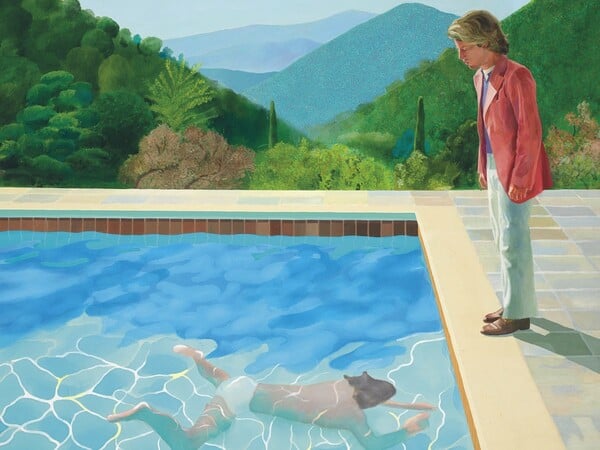

So what if he is one of the most expensive artists in the world? maybe “Portrait of an Artist (combined with two figures)” It sold for $90 million, but he himself seems restless, losing not a trace of the excitement he had as he began to discover the world, from Los Angeles to Yorkshire and Normandy, where he lives today, from his experiments with perspective to photography. Such as “Drawing with a Camera,” when he captured the passage of time in his Polaroid collages and the joy of spring on his iPad.

Hockney continues to innovate and create beauty and awe, showing us often that drawing can beautifully and vividly convey the relentless energy of the gaze. Even today, his works exude freshness, youth, wisdom, awareness of the joys of nature, life and simplicity, which he acquired through his long journey through time. His unique style always goes hand in hand with his desire for color which can also be found everywhere in his art but also with his thinking about the perception of space and its many possibilities.

An avid reader ProustHockney has come to live more and more in his studio in recent years, creating a closer link between the artist and the creative space.

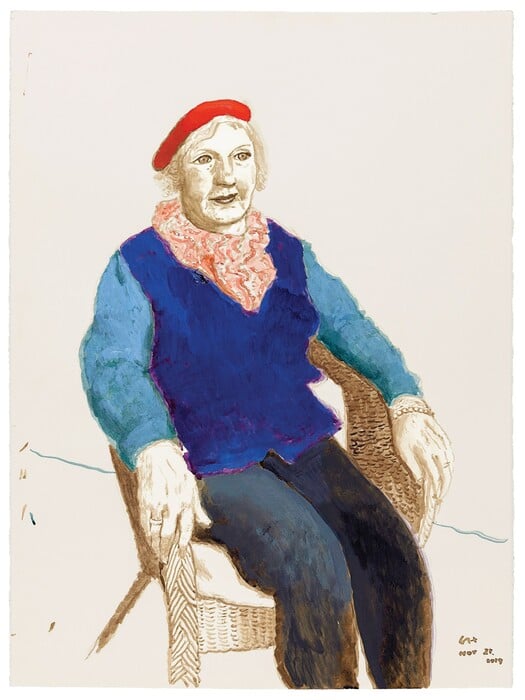

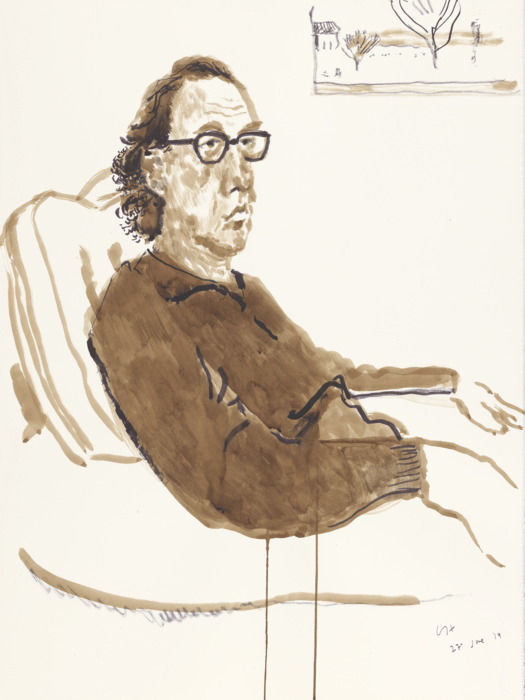

In addition to famous photos of his mother, his muse, Celia BurtwellFrom Amin Gregory Evansthe printer Maurice Payne The exhibition will also present a selection of thirty new images. Painted from nature, it depicts friends and visitors to the Normandy studio between 2021 and 2022.

Hockney’s commitment to the representation of the human figure shows how from his academic years he broke away from the mainstream of abstraction and conceptual art, and this stylistic flexibility freed him from classification. In his portraits, he approaches his subject through a different photographic mechanism and from a different perspective.

“I think I’ve always wanted to take portraits, but I felt too tied to the old, boring ideas of the Royal Academy. After all, it wasn’t Picasso and Matisse that were imposed on you, not even now. I’ve now come to the conclusion that painted portraits are more Interesting photographs: “Drawing another face is something deep within us,” says Hockney. “Everyone is interested in faces.”

In the five portraits of people that form the backbone of the exhibition, with the people closest to him sitting opposite him, the trajectory of his art over six decades is revealed. In 2019, Hockney updated his self-portraits for this exhibition.

Their most recent images in ink or color are shown together and the effect is haunting, it’s like the end of a film where you see the characters as they are now, long after their youthful adventures. His chic and funny friend, Celia Burtwell, looks on quietly at us, a kohl-rimmed 1970s character with the fashion sense of the era. She appears again in an armchair in 2019, an 80-year-old woman wearing a red hat.

Gregory Evans, with his delicate, boyish beauty, transforms over time into a solemn elderly figure as he appears to squint slightly through his spectacles, and master printmaker Maurice Payne, who collaborated with Hockney on several prints of him, retains the meditative expression of an engraving from 1998. Hockney captured each A marker of time in candid studies of the people he loved in the intervening decades.

The exhibition is completed by colored pencil drawings created in Paris in the early 1970s, composite Polaroid photographs from the 1980s, and a selection of drawings from an intense period of contemplation during the 1980s, when the artist painted a self-portrait every day of two people. Months.

About 150 works from private and public collections make up the exhibition, and are complemented by his previously unseen early works such as the designs for the seminal print series A Rake’s Progress (1961-63), inspired by the series of prints of the same name by William Hogarth (1697-64), and notebooks From Hockney’s time at Bradford School of Fine Art in the 1950s, My Parents and Myself, an earlier version of My Parents, has been rediscovered by the artist when selecting projects for the 2020 exhibition.

“The renewed exhibition fulfills the promise I made to David in March 2020 that we would return to his wonderful gallery in better days. Hockney is one of the most respected and internationally recognized artists today, and to see his new pictures created over the past two years, which demonstrate his ongoing creativity and creative power, is “A testament to his constant and constant creativity. That references both tradition and technology – from Ingres to the iPad.” Nicholas CullinanDirector, National Portrait Gallery, London.

“Wherever he is, Hockney’s true home is his sketchbook. The design allows him to keep what he loves. This exhibition reveals, with absolute freshness, an artist full of curiosity about himself and others.” Hockney enjoys inventing, but he never loses sight of his simple subject: to Be alive,” wrote Jonathan Jones in The Guardian.

Hockney has the confidence to play games like his “master”, Picasso, constantly changing his style in search of the elusive truth.

“I went to art school in Bradford when I was 16. For four years we just painted from nature, and it teaches you to look. That’s the plan. It teaches you to look and wonder about things. Someone would sit next to my drawing and then draw a shoulder or something Like that, I could see that they saw more than I saw. “So when I went back to my drawing, I looked more closely,” Hockney tells The New Yorker.

“This tendency is reflected in Hockney in always having a notebook with him, working only from nature, and recording what he sees before him. It also states the autobiographical nature of his work,” wrote Roberta Smith in the New York Times when part of the Today exhibition moved to America in October 2020 in Morgan Library and Museum: “He paints the people he knows and cares about, as well as the landscapes and homes he inhabits.”

It is noteworthy that after thirty-five years in sunny California, Hockney found new inspiration in the dramatic seasonal changes of the Norman landscape. In 2020, he began drawing daily on his iPad, documenting the poplars and fruit trees on the property as their first blossoms appeared. She’s been posting uplifting and comforting posts on social media during the pandemic, talking about spring.

A selection of the enlarged prints were displayed at the Royal Academy of Arts in London last summer, in an exhibition entitled “The Arrival of Spring.” A more recent exhibition of iPad paintings, at the Musée de L’Orangerie in Paris, provided a yearly record of the seasons, from spring to a rare snow day. It was inspired by the Bayeux Tapestry, a medieval embroidery depicting the Norman conquest of England, which is in a museum near his home.

In an age when we are bombarded with images of people, and endless selfies, Hockney’s photographs are something entirely different, they make us stop and look another way, if that has any meaning today.

It challenges us to look behind his happy images from the beginning to the present day and underscores the fact that they conceal a very serious question about the challenges of translating the world, time and space into two dimensions. To notice other colors in the rippling light in the pool, the whistle of watering cans on the green grass, the boy looking back in his bed, the flat facades of California buildings.

Hockney’s visual intelligence is more than evident, but it is not just that. His presence confirms the persistence of love in our lives and the role of art in making us notice, like him, a little differently about what is happening around us.

The art exhibition David Hockney: Drawing from Life will run from 2 November 2023 to 21 January 2024 at the National Portrait Gallery, London.

With information from the National Portrait Gallery, the Morgan Library and Museum, The Guardian, The New York Times, and The New Yorker

More Stories

In Greece Porsche 911 50th Anniversary – How much does it cost?

PS Plus: With a free Harry Potter game, the new season begins on the service

Sony set to unveil PS5 Pro before holiday season – Playstation