Just 500 kilometers from the Black Sea, Russia’s war in Ukraine is raging. Since the invasion in February 2022, Western countries have imposed sweeping sanctions on Moscow in an effort to isolate it from luxury goods and dual-use goods that can be reused on the battlefield. Meanwhile, the Group of Seven (G7) industrialized nations have imposed a cap of $60 a barrel on Russian crude oil, threatening severe penalties for traders who break the rules.

But analysts and policymakers fear that not enough is being done, and helping Russia get what it wants has become very lucrative for intermediaries, companies and countries, who provide such services and, of course, bear the corresponding risks.

Russia: Easily Bypasses Sanctions – How It Got Half a Billion Dollars in Microchips

In an effort to understand how Putin’s “smuggling” gets away with sanctions, POLITICO spoke to Yoruk Izik, a researcher at the Middle East Institute, a Washington-based think tank.

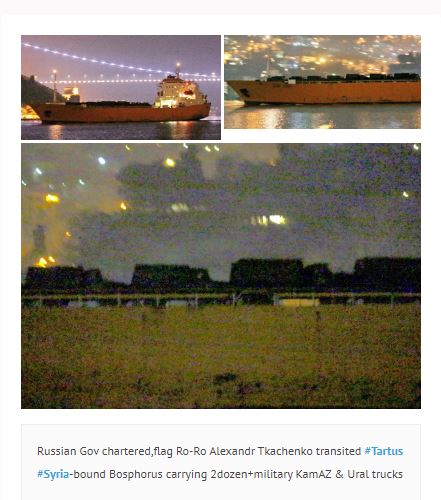

Izik lives in Istanbul and runs the Bosphorus Observer, which logs traffic in the Bosphorus Strait, and which has become a valuable aid to all concerned with the Kremlin’s supply routes.

For more than a decade, it has tracked the comings and goings of tens of thousands of grain trucks, container ships and warships along the Bosphorus each year.

According to Politico, the 52-year-old analyst has presented countless documents revealing Russia’s drive to quietly acquire military goods and equipment — while preserving energy and agricultural exports.

Izik says that Russian ships often spread false information saying that the ship was heading from one innocent place to another. Then they turn off tracking and/or spoof their location. Along the strait there is endless traffic, but when you look you will see that the ship is not there, which in itself says a lot.

But it is very difficult to keep track of what comes from Europe to Russia and back. Russia is trying to adapt to increasingly tough sanctions, and once new controls are in place, it finds a way around them. Experts point out that Turkey is the gateway to this kind of trade, especially for European consumer goods.

According to statistics compiled by POLITICO’s Trade Data Monitor analytics platform, Turkey is Russia’s fifth largest source of imports, sending more than $3.6 billion in goods and merchandise last year alone. Machinery and electronic components are among its biggest exports for 2023, rising 200% and 183% respectively in the first six months of this year. This does not even include supplies that simply pass through the Bosporus without ever officially entering Turkey.

Ankara is a mediator in the conflict, but on the other hand it provides a convenient geographic center for the re-export of goods that Moscow needs, from oil and diesel to military equipment. For Russia, this comes at a cost – but for now it’s profitable and it wants to win the war of attrition by biting into it at the right time.

Shadow fights?

Meanwhile, a so-called shadow fleet of hundreds of aging oil tankers has appeared on the global market over the past year to boost embargoed Russian energy exports and sell oil above the cap, giving the Kremlin much-needed revenue to pay its forces and buy weapons. . Without proper maintenance or insurance, they often shut down their transponders to hide their fuel source or perform ship-to-ship transfers to confuse those watching from afar.

In June, the European Union moved to ban these ships from its ports – but many of them continue to sail through the Bosphorus.

Issyk reported that the Shadow Fleet was all under the flag of the Marshall Islands and was wiped out thanks to successful American diplomacy. Then, overnight, the entire Shadow Fleet switched to the flag of Gabon.

With warnings that a detour could prolong the war, and cost more Ukrainian lives, Brussels is stepping up pressure to plug the existing loopholes. People like Isik are helpful but they can’t be ubiquitous

Worse yet for the shipping industry, unprecedented Western sanctions mean unsuspecting companies may inadvertently flout existing rules. ”

Anyone dealing with ships suspected of this type of activity, as well as a vessel disrupting transfers or making an undeclared ship-to-ship transfer, could face criminal charges, fines or confiscation of their goods. If a container subject to transit embargoes stops in Russia unplanned, becomes unmarketable and without due diligence, large companies may be caught in it.

with approval @ US Treasury To provide services to # IranMinistry of Defense, IRISL Mosakhar Darya, Iranian-flagged container ship, Daisy (x-Shahr-e Kord) crossed the Bosphorus Strait towards the Mediterranean on its way from Shahid Rajaee, Jebel Ali, #Latakia #SyriaFrom Constanta to Misurata, Libya pic.twitter.com/cY8ugt1t4W

– YorukIsik August 13, 2023

Play both sides

Of greater concern are ships that are said to be secretly supplying Russia’s armed forces. Some ships are now disguised as merchant ships, but they carry the equipment of the Russian Armed Forces and do not fly a naval flag. According to Işık, Turkey does not inspect these ships.

Despite being a NATO member, Turkey has refused to impose sanctions on Moscow, instead hosting a series of ill-fated peace talks and boosting economic ties with both sides. The policy appears to reflect public opinion within the country, where, according to a survey by Aksoy Research last year, nearly two-thirds of Turks worry the war will have a negative impact on their country — but 80 percent think it should stay. neutral.

As part of efforts to insulate itself from the fallout from the conflict, Ankara has also backed the UN-brokered grain deal, which is credited with helping move food from embattled Ukraine’s ports to the developing world. Its collapse after the Kremlin’s withdrawal last month raised fears of famine and led to a wave of Russian attacks on Ukraine’s export infrastructure. Turkey’s National Security Council has since warned that tension in the Black Sea is “in no one’s interest”, but stopped short of calling for the two sides to return to the negotiating table.

The Turkish government would prefer to see predictability instead, Ryan Gingeras, a professor at the US Naval Postgraduate School, told Politico. They have supported shipments of grain stolen from Ukraine – they have made sure to maintain good relations with Moscow, as well as with Kiev, but the collapse of the grain deal shows the limits to which Ankara can wield influence. Black Sea”.

War on the waves

Ukraine now seems intent on dealing with the threat posed by Russia itself.

Last week, Kiev declared the waters around Russia’s Black Sea ports a “war danger zone” from August 23 until later, and Ukraine now considers Russian ships in the Black Sea our military targets.

Meanwhile, the Ukrainian Armed Forces reportedly struck the Russian oil tanker Sig with a drone, severely damaging it. The ship, which was approved by the US Treasury Department in 2019, was sailing near occupied Crimea in Ukraine, with 43,123 barrels of fuel oil on board.

“The Sage is a ship that, along with its sister ship the Yaz, has been assisting Russia’s armed forces for more than half a decade now. The strike on the Sage, a secretive Russian naval service vessel carrying kerosene from refineries in occupied Crimea, is damaging to Russian logistics In Syria, which harms the profits of the elites linked to the Kremlin who make money from this trade, and reduces the money used to pay them. Special soldiers, ”Izik emphasized.

But for Isik, Istanbul is not just a place to watch the war unfold – it holds the key to ending it.

“This city has been here for thousands of years because of the waterway,” said the Turkish analyst. “If you control the water, you control the trade – and then you decide how the world works.”

“Hipster-friendly coffee fanatic. Subtly charming bacon advocate. Friend of animals everywhere.”

More Stories

F-16 crashes in Ukraine – pilot dies due to his own error

Namibia plans to kill more than 700 wild animals to feed starving population

Endurance test for EU-Turkey relations and Ankara with Greece and Cyprus