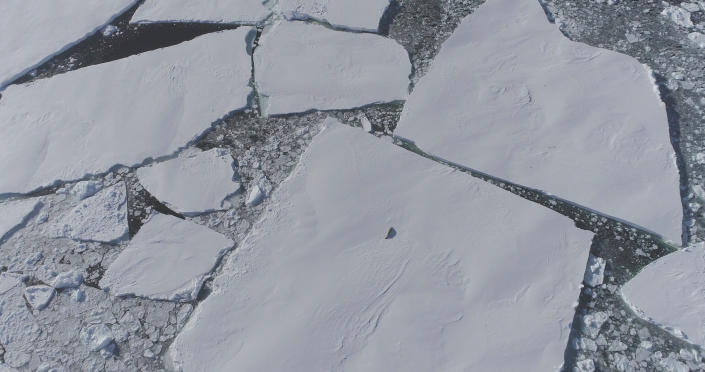

A disintegrating Antarctic glacier the size of Florida could raise global sea levels significantly faster than previously expected, according to a study published Monday in the journal. natural earth sciences.

A group of international researchers has mapped the historical footprint of the Thwaites Glacier in West Antarctica – nicknamed the “Doomsday Glacier” because of the huge impact that its collapse would have due to warmer temperatures. They found “exceptionally fast rates of past retreat,” including – at some point in the past two centuries – a period in which the glacier retreated by 1.3 miles per year. This is twice as fast as the rate of decline detected in the 2000s.

“Thwaites is really sticking with its nails today, and we should expect to see big changes on small time scales in the future – even from year to year – once the glacier retreats beyond a shallow ledge at its bottom,” said British Antarctica’s Robert Larter of the study, author of the study. Study participant, in a new version that accompanied the publication of the study.

According to the scientists involved in the research, the ramifications of this melting could be enormous. “You can’t take Thwaites and leave the rest of Antarctica intact,” said Alistair Graham, a marine geologist at the University of South Florida and one of the study’s authors.

The Thwaites Glacier is one of the widest rivers on Earth, but it’s just a tiny piece of the West Antarctic ice sheet, which contains enough ice to raise sea level by up to 16 feet if it melts, according to NASA.

Thwaites lies at the bottom of the ocean, rather than on land, which makes it particularly vulnerable to melting due to the warmer waters. In 2020, scientists found that warm water was melting The lower reaches of Thwaites. Studies have already shown that up to 90% More global warming from greenhouse gas emissions is being absorbed by the oceans and the oceans are warming faster than previously thought.

Thwaites’ melt already accounts for about 4% of the annual sea level rise, which is currently approximately 0.12 to 0.14 inch per yearAccording to the Environmental Protection Agency. More than 40% of the world’s population lives within 60 miles of the coast, and many are in areas flooded with sea level rise of more than 3 feet.

This isn’t the first warning sign that Thwaites may be in a precarious state thanks to rising global temperatures. Satellite images taken late last year show that the ice shelf in the eastern part of the glacier is showing signs of cracking.

“Things are developing really fast here,” said Ted Schampos, a glaciologist at the University of Colorado Boulder and president of Thwaites Glacier Collaboration International. Reporters at that time. “It’s hard.”

The researchers involved in that study warned that the ice shelf could detach from the sea floor, potentially causing the ice shelf to collapse, a process that would then lead to further melting. “It would become self-sufficient and cause a significant amount of retreat for some glaciers” including Thwaites, said Anna Crawford, a glaciologist at the University of St Andrews, at the time that study was released.

Graham said his team cannot confidently predict whether the Thwaites glacier will dissolve completely, but that reducing emissions will be critical to minimizing risks.

“Right now, we can do something about it — especially if we can prevent the ocean from warming,” he said.

“Avid problem solver. Extreme social media junkie. Beer buff. Coffee guru. Internet geek. Travel ninja.”

More Stories

In Greece Porsche 911 50th Anniversary – How much does it cost?

PS Plus: With a free Harry Potter game, the new season begins on the service

Sony set to unveil PS5 Pro before holiday season – Playstation