Editing – Editing: Stelios Vasiloudis

Scientists have discovered “dark oxygen” produced deep in the ocean, apparently from pieces of metal on the sea floor.

Advertising space

About half the oxygen we breathe comes from the oceans. Before this discovery, it was understood that marine plants make it through photosynthesis, which requires sunlight. But at a depth of 5 kilometers, where sunlight cannot penetrate, oxygen appears to be produced by natural mineral “nodules” that break down seawater — H2O — into hydrogen and oxygen.

Several mining companies plan to harvest these nodules, which marine scientists fear could disrupt the newly discovered process — and harm any marine life that depends on the oxygen they produce.

“I first saw this in 2013, where a huge amount of oxygen is being produced on the seafloor in complete darkness,” lead researcher Professor Andrew Sweatman, from the Scottish Association for Marine Science, explained. “I ignored it because I was taught that you only get oxygen through photosynthesis. Eventually I realised that I hadn’t known about this huge discovery for many years,” he told BBC News.

Advertising space

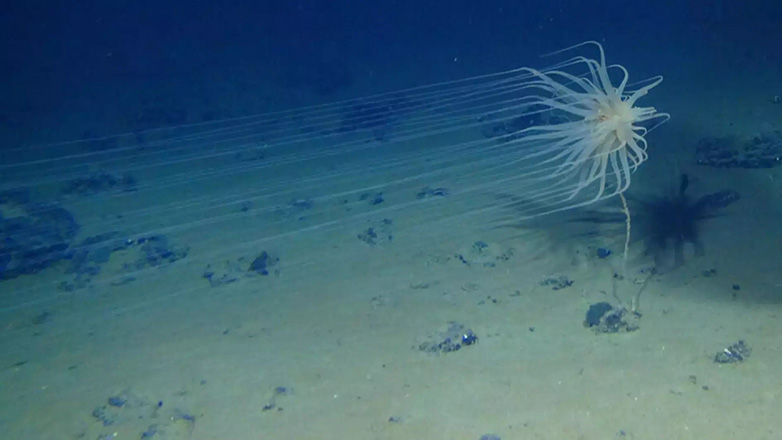

He and his colleagues conducted their research in a deep-sea area between Hawaii and Mexico, part of a vast strip of seafloor covered in these mineral nodules. The nodules form when minerals dissolved in seawater collect on shell fragments—or other debris. It’s a process that takes millions of years.

Because these nodules contain minerals such as lithium, cobalt and copper – essential for making batteries – several mining companies are developing technology to collect them and bring them to the surface. But Professor Sweatman says the “dark oxygen” produced by these organisms could also support life on the seafloor. His discovery, published in the journal Nature Geoscience, raises new concerns about the risks of proposed deep-sea mining projects.

The scientists discovered that the mineral nodules are able to produce oxygen precisely because they act like batteries. “If you put a battery in seawater, it starts to foam,” explains Professor Sweetman. “This happens because the electric current actually breaks the seawater into oxygen and hydrogen (which are the bubbles). We think this is what happens with these nodules in their natural state.”

“It’s like a battery in a flashlight. If you put a battery in, it doesn’t light up. You put two in and you have enough voltage to light the torch. So when the nodules on the seafloor come into contact with each other, they work together — like many batteries together.” The researchers tested this theory in the lab, where they collected and studied mineral nodules the size of a potato. Their experiments measured the voltage across the surface of each mineral block, or the strength of the electric current. They found that it was roughly the same voltage as a standard AA battery.

This means that nodules on the seafloor could generate electrical currents strong enough to break apart, or electrolyze, seawater molecules. The researchers believe that the same process—battery-assisted oxygen production that doesn’t require light or biological processes—could occur on other planets, creating oxygen-rich environments where life could thrive.

The Clarion-Clipperton Zone, where the discovery was made, is already being explored by several deep-sea mining companies, which are developing technology to collect the nodules and transport them to surface ships. The US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration has warned that such seabed mining could “destroy seafloor life and habitats in mined areas.”

More than 800 marine scientists from 44 countries have signed a statement highlighting the environmental risks and calling for a moratorium on mining. New species are constantly being discovered in the deep ocean – it’s often said that we know more about the surface of the moon than the deep sea. This discovery suggests that the nodules themselves could provide oxygen to support life there.

Professor Murray Roberts, a marine biologist from the University of Edinburgh, is one of the scientists who signed the petition to stop seabed mining. He told the BBC: “There is already overwhelming evidence that strip mining in deep sea nodule fields will destroy ecosystems that we barely understand.”

“Given that these fields cover vast areas of our planet, it would be crazy to proceed with deep-sea mining knowing that they could be an important source of oxygen production,” Professor Sweetman added. “I don’t see this study as the end of mining.

But we must continue to explore in more detail and we must use this information and data that we collect in the future. If we are going to go deep into the ocean and extract it, at least we must do it in an environmentally friendly way.”

Source: BBC News

“Avid problem solver. Extreme social media junkie. Beer buff. Coffee guru. Internet geek. Travel ninja.”

More Stories

In Greece Porsche 911 50th Anniversary – How much does it cost?

PS Plus: With a free Harry Potter game, the new season begins on the service

Sony set to unveil PS5 Pro before holiday season – Playstation