By Mark Champion

This is not the first time Ukraine has had problems with Berlin’s support. It also has problems with France, the United States and even the United Kingdom. All of this goes a long way to explaining why Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy risked sending troops to fight in Russia when he barely had enough to hold the front line at home.

It would be easy to single out Germany, a country that initially provided Ukraine with nothing more than helmets to help defend against a full-scale invasion by Russia in February 2022. Chancellor Olaf Scholz’s bold speech to reshape German energy and security policies changed all that. But with the Frankfurter Allgemeine reporting this week that the country’s finance ministry plans to halve its aid budget for Ukraine next year and then cut it even more after that, Solz’s “U-turn” looks more like a U-turn.

Following Berlin’s issuance of an arrest warrant for a Ukrainian national accused of sabotaging the Nord Stream gas pipeline from Russia to Germany in September 2022, you might also think that the alleged cuts were retaliatory. They are not, and not because the government says no decisions on cuts have been made yet. The answer is much simpler: a dysfunctional coalition government and a finance minister clinging to absurdly restrictive fiscal rules.

The bottom line is that you can’t reach a tipping point that changes Germany’s business model and security model without spending money. The country is experiencing some serious economic turmoil, but it remains rich enough to maintain funding for Ukraine, increase defense spending, and take care of social needs at the same time.

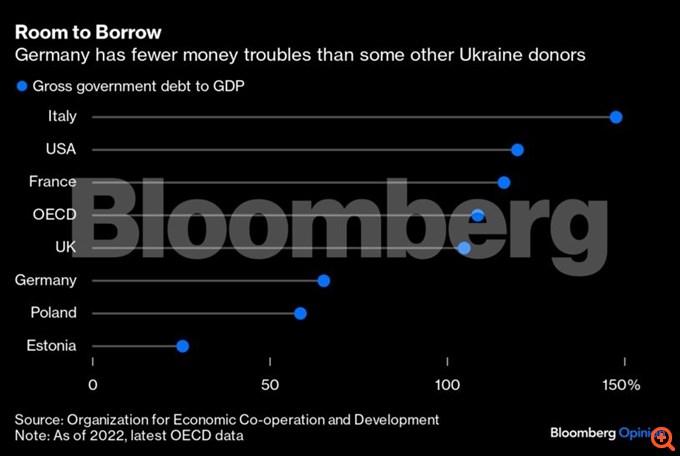

The problem is much broader than Germany’s, even if Berlin’s case seems extreme, because the government, unlike some other countries, has a lot of fiscal space. And the amounts involved – contrary to populist rhetoric – are tiny: for Germany, €8 billion ($9 billion) next year, or 0.002% of GDP. So the issue is not so much a lack of resources as political dysfunction, the rise of pro-Russian populists, and a lack of will. Zelensky’s attack on Kursk is intended to change that.

The unwillingness to acknowledge that Russian threats to unleash nuclear war are hollow, and that we should not allow them to stand in the way of Ukrainian equipment, is a grave failure.

“We are now witnessing a major ideological change, that is, the whole naive concept of so-called red lines in relation to Russia, which dominated the assessment of the war by some partners, has collapsed these days somewhere near Sunja,” Zelensky said in his annual address to the country’s diplomatic staff this week, referring to the key Russian city that Ukrainian forces have seized.

To illustrate his point, Zelensky said the entire Kursk operation would not have been necessary if the allies had lifted restrictions on using their long-range missiles to strike Russia’s main firepower advantages where they are, behind the front lines. The American ATACMS surface-to-surface missiles, the British, French and German Storm Shadow missiles, and the SCALP_EG and Taurus cruise missiles, respectively, would allow Ukraine to more effectively destroy bridges, arms depots and especially airfields from which Russian aircraft armed with bombs take off.

These weapons are among the most effective tools Russia has had since the war began. These are unguided bombs weighing up to 1.5 tons, and they are being dropped on Ukrainian forces at a rate of 130 to 150 a day, Mykola Beliskov, a researcher at the National Institute for Security Studies in Kyiv, told me. They are devastating, especially when combined with Russia’s overwhelming superiority in artillery shells.

Much of the attention to Zelensky’s game has rightly focused on whether the move could force Russian President Vladimir Putin to withdraw troops from the front lines in the Donbas region of eastern Ukraine. If so, the operation would have been a military success, “relieving” pressure on a front that had been slowly retreating.

So far, that hasn’t worked. Instead, Russia has intensified its attacks in the Donbas, while assembling a motley crew of forces from elsewhere to halt the Ukrainian advance on Kursk. If the Kursk offensive—as Zelensky clearly hopes—can rally allied support and arms supplies while convincing Western leaders to lift restrictions on the use of their long-range missiles against targets on Russian territory, it could achieve much more with this Ukrainian threat.

By neutralizing Russia’s key assets, Ukraine would be able to “relieve” the pressure on its defenses even without Russia diverting its forces. It could also leave Kiev with a small amount of territory to trade in future negotiations. This optimistic scenario would ensure tactical military gains, as well as strategic gains that could influence the outcome of the war as a whole.

If Zelensky’s gamble fails to mobilize the West or even ease restrictions on long-range weapons, these potential strategic gains will be lost. Ukraine is also likely to lose the important transport hub of Pokrovsk in the Donbas, and Putin will be close to occupying all of the Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts, which he annexed just before his invasion. Ukraine will likely at some point seek peace on terms that, as a similar deal in 2014 proved, will encourage Putin to fight back later.

But that doesn’t have to happen. In fact, Russia faces fewer political challenges in maintaining the war because Putin can control what the Russian public sees and hears, says Stefan Meister, an expert on Russia, Eastern Europe and Central Asia at the German Council on Foreign Relations: “We are in a different reality of rising populism.” That requires governments to do a better job of showing their publics that they have a viable plan to end the war without letting Putin win.

Germany plays a special role in this whole situation because it has become the second-largest supplier of arms to Ukraine after the United States, including some of the most effective weapons, such as the IRIS-T air defense system and the Taurus cruise missile with a range of 500 kilometers. It has not even delivered them for fear of provoking a Russian escalation. However, in his evening address to the nation on Sunday, Zelenskyy blamed France, the United Kingdom and the United States for delaying promised arms shipments.

Everyone involved, including Zelensky, knows that this war will end at the negotiating table. The question is on what terms. It is up to Western leaders to finally define securing a strong negotiating position for Ukraine as a victory, and to devise an economic and military strategy to achieve it. They have the means, and they can start by lifting the restrictions on these long-range missiles.

Performance – Editing: Stathis Ketejian

“Hipster-friendly coffee fanatic. Subtly charming bacon advocate. Friend of animals everywhere.”

More Stories

F-16 crashes in Ukraine – pilot dies due to his own error

Namibia plans to kill more than 700 wild animals to feed starving population

Endurance test for EU-Turkey relations and Ankara with Greece and Cyprus